Whiskey Around the World: A Beautiful Look at Global Styles & Stories

Whisk(e)y is the alchemy of grain, water, time, and oak—a spirit born from fermented mash and patiently matured in wooden barrels. From its medieval roots in Ireland and Scotland, it has travelled the globe, carrying with it tales of monasteries, frontier stills, and modern laboratories.

Today that journey pours out in an astonishing palette of styles. Bourbon offers caramel‑soaked warmth, rye crackles with spice, and smoky Islay malts evoking sea‑sprayed peat fires share shelf space with the silken precision of Japanese blends. Even newcomers from India, Taiwan, and Australia push boundaries by harnessing tropical heat, red‑wine casks, and native grains.

Whether you prefer a contemplative dram neat or a lively cocktail, whisk(e)y rewards slow exploration. This guide maps the world’s major categories and uncovers the craft, culture, and flavors that make each one unforgettable.

Whisk(e)y Basics

Understanding whisk(e)y starts with grasping its fundamental creation process. The journey from grain to glass involves several crucial steps—each contributing significantly to the flavor, aroma, and character of the final spirit.

The Core Production Process

Whisk(e)y begins with selecting grains, typically barley, corn, rye, or wheat. These grains are milled, combined with water, and heated to create a mash. The starches in the grains are converted into fermentable sugars during this step. Yeast is then added, fermenting the sugars into alcohol, creating a liquid known as “wash.”

The wash is distilled—usually twice or thrice—to increase the alcohol content and refine the spirit. This distilled liquid, known as new-make spirit, is then aged in wooden barrels, typically oak, for a minimum period defined by regional laws and traditions, imparting flavors and colors from the wood.

Whisky vs. Whiskey: What’s in a Spelling?

The variation in spelling primarily depends on regional traditions. “Whisky” without an “e” is commonly associated with Scotland, Canada, and Japan, while “whiskey” with an “e” denotes spirits from Ireland and the United States. Though subtle, this spelling difference is culturally significant and often indicative of specific production styles and heritage.

Factors Influencing Flavor and Quality

Whisk(e)y’s character is shaped by grain choice, water source, distillation methods, maturation processes, and local climate. Barrels—previously used or new, charred or uncharred—also dramatically influence the spirit’s final taste, ranging from sweet and fruity notes to robust and smoky nuances.

Scotch Whisky

Scotch whisky is synonymous with sophistication and depth. Governed strictly by Scottish law, this type of whisky must mature in oak barrels for at least three years, ensuring exceptional quality and complexity.

Styles of Scotch Whisky

Scotch whisky primarily falls into five categories:

- Single Malt Whisky: Produced from malted barley at a single distillery.

- Single Grain Whisky: Made at one distillery from various grains, including malted barley.

- Blended Malt Whisky: A combination of single malts from multiple distilleries.

- Blended Grain Whisky: A blend of grain whiskies from various distilleries.

- Blended Whisky: A combination of single malts and grain whiskies, often balancing smoothness and complexity.

Flavor Spectrum

Scotch whiskies exhibit a broad flavor range—from the subtle and delicate to the heavily peated and smoky. Regions like Islay produce robust, smoky whiskies, whereas the Highlands and Speyside offer fruity, floral, and elegant expressions.

Irish Whiskey

Irish whiskey, one of the world’s oldest distilled beverages, is renowned for its smoothness and approachability. Traditionally triple-distilled, this whiskey style typically offers a cleaner, smoother, and more delicate palate.

Irish Whiskey Styles

- Single Pot Still: Distilled from malted and unmalted barley, providing a creamy texture and spicy notes.

- Single Malt: Similar to Scotch single malt but typically smoother and lighter.

- Grain Whiskey: Distilled primarily from maize or wheat, often light and sweet.

- Blended Whiskey: Combining pot still, malt, and grain whiskies for versatile, balanced profiles.

Revival and Global Popularity

Irish whiskey has seen significant growth and innovation in recent decades, driven by renewed interest in heritage brands and craft distilleries. Its signature smoothness and versatility continue to captivate global audiences, fueling a renaissance in Irish whiskey production and appreciation.

American Whiskey

The United States boasts one of the most diverse whiskey landscapes in the world, shaped by expansive geography, immigrant influence, and innovative spirit regulations. American whiskey must be distilled within U.S. borders, and while styles vary widely, they share a common theme: bold flavors that reflect the nation’s agricultural bounty and pioneering mindset.

From corn‑rich bourbons to spice‑forward rye and charcoal‑smoothed Tennessee bottlings, each expression demonstrates how mash bills, barrel treatments, and state laws combine to create unmistakably American identities.

Bourbon

Legally, bourbon must contain at least 51 % corn in its mash bill, be distilled to no more than 80 % ABV (160 proof), and aged in new, charred American oak barrels. These parameters produce classic notes of vanilla, caramel, toasted coconut, and baking spice.

Because the wood is always brand‑new and heavily charred, bourbon often matures relatively quickly, developing a deep amber hue and rich sweetness even in as little as four years. Kentucky remains the historical heartland, though excellent bourbons now hail from states as far‑flung as Texas, New York, and Colorado.

Limited‑release “single barrel” and “cask strength” bottlings allow enthusiasts to experience bourbon in its most unfiltered form, offering concentrated flavors and unique barrel‑to‑barrel variation.

Tennessee Whiskey

Tennessee whiskey follows nearly all bourbon regulations but adds a signature step known as the Lincoln County Process: fresh distillate trickles slowly through thick layers of sugar‑maple charcoal before barreling. This filtration removes some harsher congeners and imbues the spirit with a distinctive mellowness and subtle smoke.

Most Tennessee whiskey ages a minimum of four years, with flagship producers like Jack Daniel’s and George Dickel popularizing the style worldwide. While labeling as “bourbon” is legally permissible, Tennessee distillers fiercely protect the regional identity of their charcoal‑softened whiskey.

Rye Whiskey

Rye’s mash bill must be at least 51 % rye grain, resulting in a markedly different flavor profile—think cracked black pepper, clove, mint, and dried fruit. Prior to Prohibition, rye dominated American whiskey production, particularly in Pennsylvania and Maryland.

Today’s revival has seen craft and heritage distillers re‑embrace the grain, experimenting with heirloom varietals and unique barrel finishes. Rye’s assertive spice also makes it a favorite for classic cocktails like the Manhattan and Sazerac, where its robustness stands firm against sweet vermouth, bitters, or absinthe.

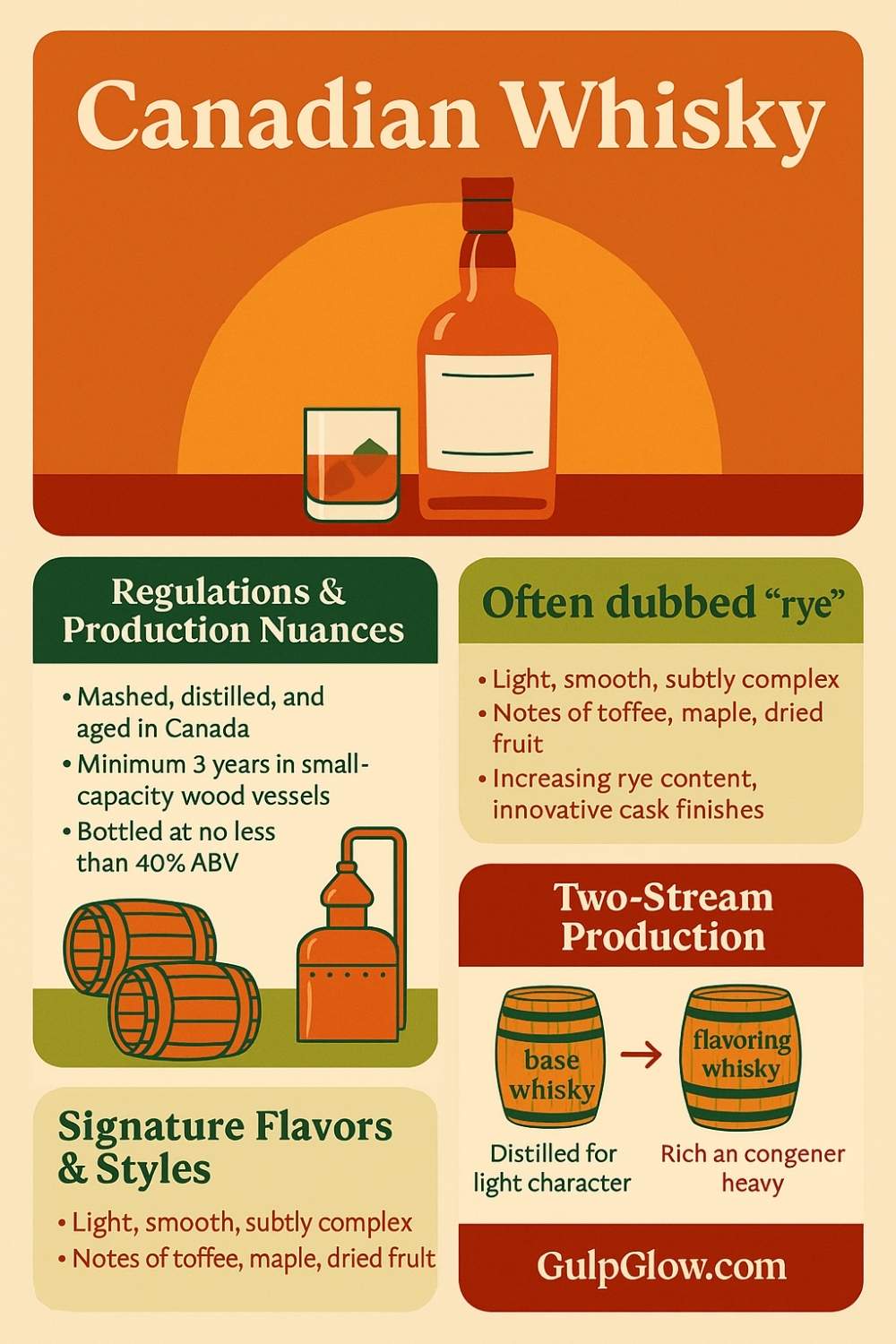

Canadian Whisky

Often dubbed “rye” by Canadians regardless of actual rye content, Canadian whisky is typically distilled in large column stills from a base of corn and rye, then matured for a minimum of three years in oak barrels.

Unlike America’s grain‑recipe‑strict labeling, Canada’s regulations allow master blenders exceptional flexibility: different grains are usually fermented and distilled separately, then blended post‑maturation to achieve consistent house styles.

This practice yields whiskies celebrated for their lightness, smooth texture, and subtle complexity, making them highly versatile for both neat sipping and mixed drinks.

Regulations & Production Nuances

Canadian whisky regulations stipulate that the spirit be mashed, distilled, and aged in Canada, bottled at no less than 40 % ABV, and matured in small‑capacity wood vessels (often ex‑bourbon or refill Canadian whisky barrels).

Many producers employ a two‑stream approach: a high‑proof “base whisky” distilled for light character and a lower‑proof “flavoring whisky” rich in congeners and often rye‑heavy. The two are married, along with small amounts of caramel coloring, to create the final expression.

Signature Flavors & Styles

While historically characterized as gentle and sweet, modern Canadian whisky now spans a spectrum—from approachable blends to robust, rye‑forward single barrels that rival the intensity of American counterparts. Notes of toffee, maple, dried fruit, and mild baking spice are common, with occasional hints of toasted oak or candied orange peel.

Limited‑edition releases, increased rye content, and innovative cask finishes (rum, wine, even ice‑wine barrels) are driving renewed global interest in Canada’s whisky scene.

Japanese Whisky

Japan entered the whisky arena in the early 20th century, inspired by Scottish techniques but driven by a uniquely Japanese pursuit of balance, precision, and harmony. Pioneers Masataka Taketsuru and Shinjiro Torii established a foundation that values meticulous craftsmanship—from exacting fermentation protocols to precisely controlled small‑batch blending. Today Japan’s top brands regularly win international accolades, underscoring the nation’s mastery of both tradition and innovation.

Historical Roots

Taketsuru’s 1918 apprenticeship in Scotland introduced authentic Scottish pot‑still methods to Japan. Early distilleries, notably Yamazaki (1923) and Yoichi (1934), sought to recreate the delicate fruit and subtle smoke of Highlands and Islay malts while adapting to Japan’s humid summers and dramatic seasonal shifts. Japanese whisky quickly developed its own stylistic identity: cleaner malt profiles, gentle peat, and an emphasis on balanced elegance rather than overt potency.

Modern Innovation & Diversity

Contemporary Japanese whisky incorporates a mosaic of production choices: varying barley strains (some peated, some unpeated), mash tun styles, yeast varieties, and a broad palette of cask types—American oak, Spanish sherry, Japanese Mizunara, and even ex‑umeshu barrels.

Distilleries such as Chichibu and Mars Shinshu experiment with rapid climate‑assisted maturation, while larger houses like Suntory and Nikka refine complex vatting techniques to craft multi‑layered blends. The result is a category celebrated for silky textures, orchard‑fruit sweetness, delicate spice, and occasional sandalwood‑incense notes unique to Mizunara oak.

As global demand surges, age‑statement bottlings have become scarce, prompting non‑age‑statement releases that still uphold Japan’s hallmark quality. Collectors and enthusiasts alike treasure Japanese whisky for its harmonious profile—proof that reverence for tradition, coupled with relentless innovation, can yield world‑class spirits.

Indian & Other World Whiskies

The whisk(e)y renaissance is not confined to traditional heartlands. In recent decades, distilleries across India, Taiwan, Australia, and continental Europe have emerged as dynamic players—often blending Old‑World methods with local grains, climates, and cask innovations to craft distinctive spirits. These “new world” whiskies broaden the global palate, demonstrating how terroir, climate, and creativity can drive rapid maturation and unique flavor profiles.

India’s Rapid Maturation & Diversity

India’s tropical climate accelerates whisky maturation: angel’s‑share evaporation rates can exceed 10 % per year compared with Scotland’s ~2 %. Distilleries like Amrut (Bangalore) and Paul John (Goa) leverage this heat, producing award‑winning single malts rich in tropical fruit, dark chocolate, and subtle spice within just four to five years. Recent innovators—Rampur in the Himalayan foothills, for instance—experiment with peated malt, wine cask finishes, and long rye fermentations, showcasing India’s wide flavor spectrum.

Taiwan, Australia & Beyond

- Taiwan (Kavalan): High humidity and fluctuating temperatures in Yilan enable rapid barrel interaction, yielding lush, fruit‑forward malts that have clinched “World’s Best Single Malt” titles.

- Australia (Starward, Lark, Sullivans Cove): Focus on red‑wine‑seasoned barrels and cooler Tasmanian air, delivering jammy, oak‑spiced whiskies with soft tannins.

- Europe (Sweden’s Mackmyra, France’s Brenne, Germany’s Stork Club): Employ native barley strains, juniper‑smoked malt, and Cognac casks to craft regionally expressive spirits.

Collectively, these producers illustrate how climate, barrel selection, and local grain can equal—or surpass—decades‑long Scottish aging in complexity and depth.

Choosing & Tasting Whisk(e)y

With global shelves brimming with options, selecting a bottle can feel daunting. A structured approach—considering style, flavor profile, budget, and intended consumption—helps narrow choices and enhances enjoyment.

Selecting a Bottle

- Identify preferred flavor families: light & floral, fruity & spicy, smoky & peated, or rich & dessert‑like.

- Match use case: neat sipping favors nuanced single malts; cocktail bases thrive with robust rye or bourbon; celebratory sharing might call for cask‑strength or limited editions.

- Check age statements and barrel finishes: older isn’t always better—first‑fill wine or sherry finishes can add dramatic character to younger whiskies.

- Research distillery ethos: craft micro‑producers may emphasize terroir, while large houses offer consistency.

Tasting Technique

- Glassware: A tulip‑shaped Glencairn concentrates aromas toward the nose.

- Nosing: Swirl gently, inhale slowly—first at mouth level, then closer, noting fruit, cereal, oak, or smoke.

- Palate: Sip small amounts, coating tongue; note sweetness, spice, mouthfeel, and balance.

- Finish: Pay attention to aftertaste length—short, medium, or lingering—with echoes of oak, dried fruit, or peat.

- Add water sparingly: A few drops can open hidden layers, especially in cask‑strength whiskies.

Tasting in flights—comparing three to five expressions—sharpens sensory perception and highlights regional nuances.

Glossary & Resources

A concise glossary empowers enthusiasts to decode labels and tasting notes:

- Mash Bill: Grain recipe used before fermentation.

- Cask Strength: Bottled without dilution, retaining natural barrel proof.

- Finish: Secondary maturation in a different cask to impart extra flavor.

- Angel’s Share: Portion of spirit lost to evaporation during aging.

- Single Malt: Whisky from one distillery, 100 % malted barley.

- Blended Whisky: Mixture of malt and grain whiskies from multiple distilleries.

- Peat: Decomposed vegetation burned to dry malted barley, imparting smoky phenols.

Further Exploration

- Books: The World Atlas of Whisky by Dave Broom; Whisky: A Tasting Course by Eddie Ludlow.

- Websites & Communities: Whisky Advocate, r/Scotch on Reddit, and Distiller.com provide reviews, ratings, and forums.

- Tasting Events: Annual festivals like Spirit of Speyside (Scotland), Whisky Live (global cities), and WhiskeyFest (USA) offer invaluable opportunities to sample broad portfolios.