Brandy Beyond the Grape: Cognac, Armagnac, Pisco & the World’s Fruit Spirits

Brandy is often called “fire‑wine”—a spirited transformation that captures a vineyard or orchard’s essence, then concentrates it through heat, copper, and time. From the dim alambic stills of 15th‑century France to the volcanic foothills of modern Peru, this distilled elixir has long seduced explorers, emperors, and everyday sippers with aromas of baked fruit, vanilla‑kissed oak, and a warming glow that lingers long after the glass is empty.

Yet brandy is far from a single style. Cognac courts refinement with double‑distilled Ugni Blanc and limousine‑oak elegance; rustic Armagnac whispers Gascon earth in every vintage‑dated sip. Grappa champions Italy’s waste‑nothing ethos by coaxing flavor from discarded grape skins, while Pisco retains fresh, floral vibrancy by eschewing oak altogether. Venture farther and you’ll meet Calvados—Normandy’s fermented apples reborn as liquid tarte tatin—and crystalline fruit eaux‑de‑vie like Kirsch and Slivovitz that bottle orchard blossoms unfiltered.

Whether you favor a fireside snifter of XO Cognac or a zesty Pisco Sour at sunset, understanding brandy unlocks a world where terroir, distillation technique, and barrel craft interlace to create remarkably diverse spirits. In the pages ahead, we’ll tour these storied regions, decode production secrets, and equip you to taste, pair, and select brandies with confident curiosity.

Brandy Basics

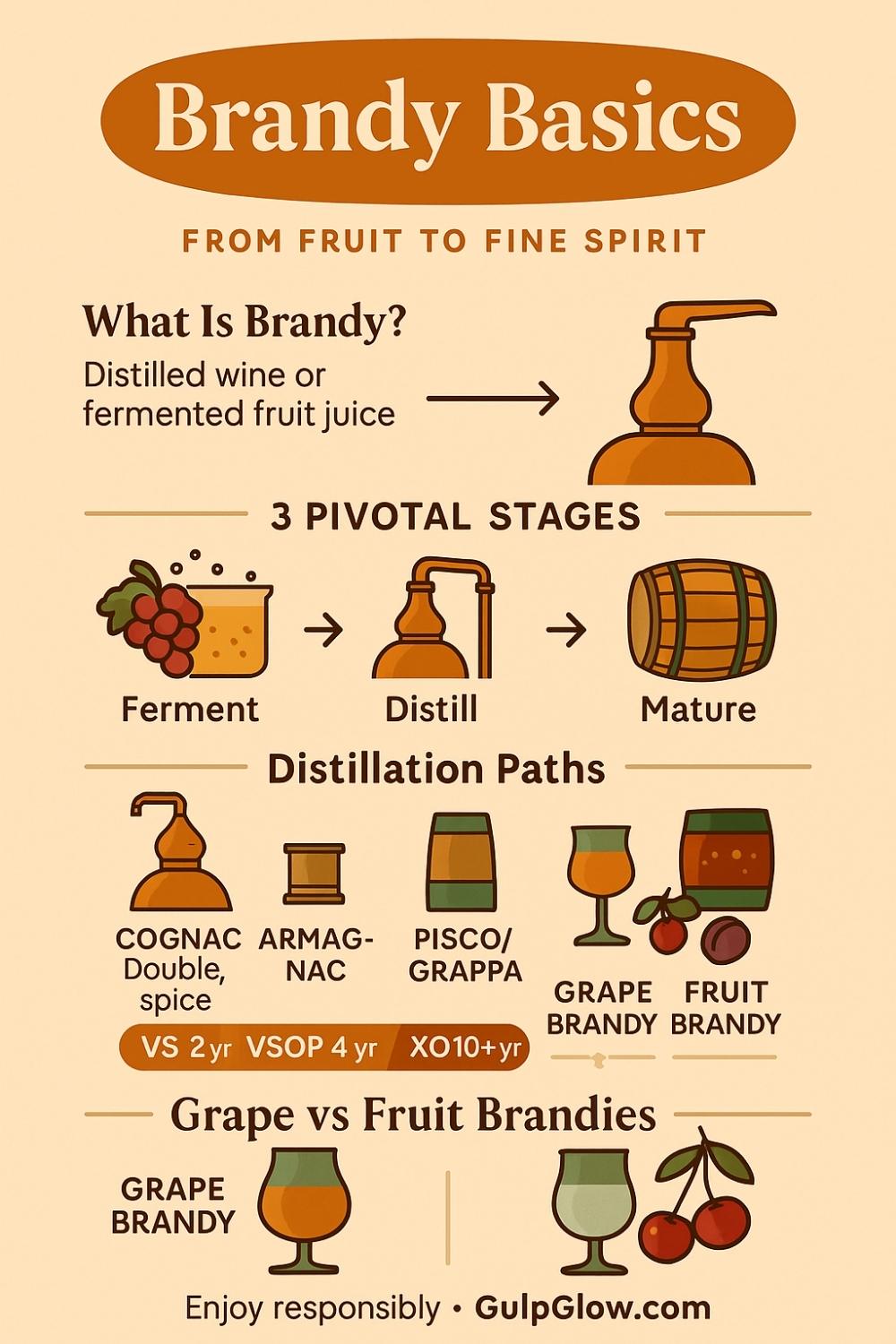

Brandy is fundamentally wine—or any fermented fruit juice—distilled to concentrate alcohol and flavor. While recipes, stills, and barrel regimens vary wildly, every brandy journey shares three pivotal stages that transform humble juice into complex eaux‑de‑vie.

From Ferment to Flame

The process begins with a base wine that is intentionally light, acidic, and often low in alcohol so grape or fruit aromatics survive distillation. In a pot still, this wine is gently heated; alcohol vapors rise, condense, and are collected as a clear spirit called “brouillis” or “low wines.”

A second distillation (Cognac) or a continuous armagnacais still run (Armagnac) refines the spirit, focusing the heart cut where congeners create depth yet remain free of harsh heads and tails.

Column stills, common in Pisco and modern Grappa, allow rapid, single‑pass distillation while retaining delicate floral esters.

Aging & Cask Choices

Fresh distillate is either bottled immediately, as with many Piscos and fruit brandies, or laid to rest in oak. New French oak imparts vanilla and spice; older barrels lend gentler tannins and oxidative rancio notes.

Some producers finish spirits in sherry, port, or even cider casks, layering dried‑fruit sweetness or orchard freshness. Age statements—VS, VSOP, XO—reflect minimum barrel time, but climatic conditions (humid Cognac cellars vs dry Peruvian bodega lofts) affect extraction speed and evaporation losses, the so‑called angel’s share.

Grape‑ vs. Fruit‑Based Brandies

EU regulations dictate that only distilled grape wine may be labeled simply “brandy,” whereas apple, cherry, or plum distillates must specify the fruit. This distinction matters in production: grape brandies often rely on oak integration, while clear fruit eaux‑de‑vie aim for crystalline purity, capturing the raw essence of orchard aromas.

Understanding the base material immediately signals what to expect on the nose and palate—oak‑laced pastry notes from Cognac, fresh blossom from Kirsch, or earthy dried‑plum depth from Slivovitz.

Cognac: The Aristocrat of Brandies

Elegant and tightly regulated, Cognac hails exclusively from France’s Charente and Charente‑Maritime départements. Distillers there have perfected a double‑distillation method in squat copper alembics that yields spirits famed for finesse, layered fruit, and silky texture.

Cognac’s production zone is subdivided into six crus—Grande Champagne, Petite Champagne, Borderies, Fins Bois, Bons Bois, and Bois Ordinaires—each defined by chalk content and microclimate. Most houses rely on the high‑acid Ugni Blanc grape, prized for retaining zesty green‑apple aromas after fermentation.

Distillation & Maturation

Between November and March, winemakers load fermented wine into charentais pot stills for two sequential distillations. The first run produces brouillis (~30 % ABV); the second, la bonne chauffe, yields a crystal‑clear eau‑de‑vie capped at 72 % ABV to preserve aromatics. Aging must last at least two years in French oak—often from Limousin or Tronçais forests—where the spirit slowly develops notes of dried apricot, vanilla, and walnut.

Grades & Styles

- VS (Very Special): minimum 2‑year cask age; lively, fruit‑driven; ideal for cocktails.

- VSOP (Very Superior Old Pale): minimum 4 years; deeper honey, spice, and floral tones.

- XO (Extra Old): 10 years minimum; lush rancio, fig, leather, and cigar‑box complexity.

Many producers also release “Extra,” “Hors d’Âge,” or single‑estate bottlings that showcase vintage nuance or specific cru character—Borderies for violet perfume, Grande Champagne for ethereal length.

Serving & Pairing

Sip Cognac neat in a tulip glass around 18 °C, or match it with blue cheese, dark chocolate, or a fine cigar. Its structure also elevates classic cocktails like the Sidecar, where citrus and Cointreau accentuate Cognac’s orange‑peel undertones.

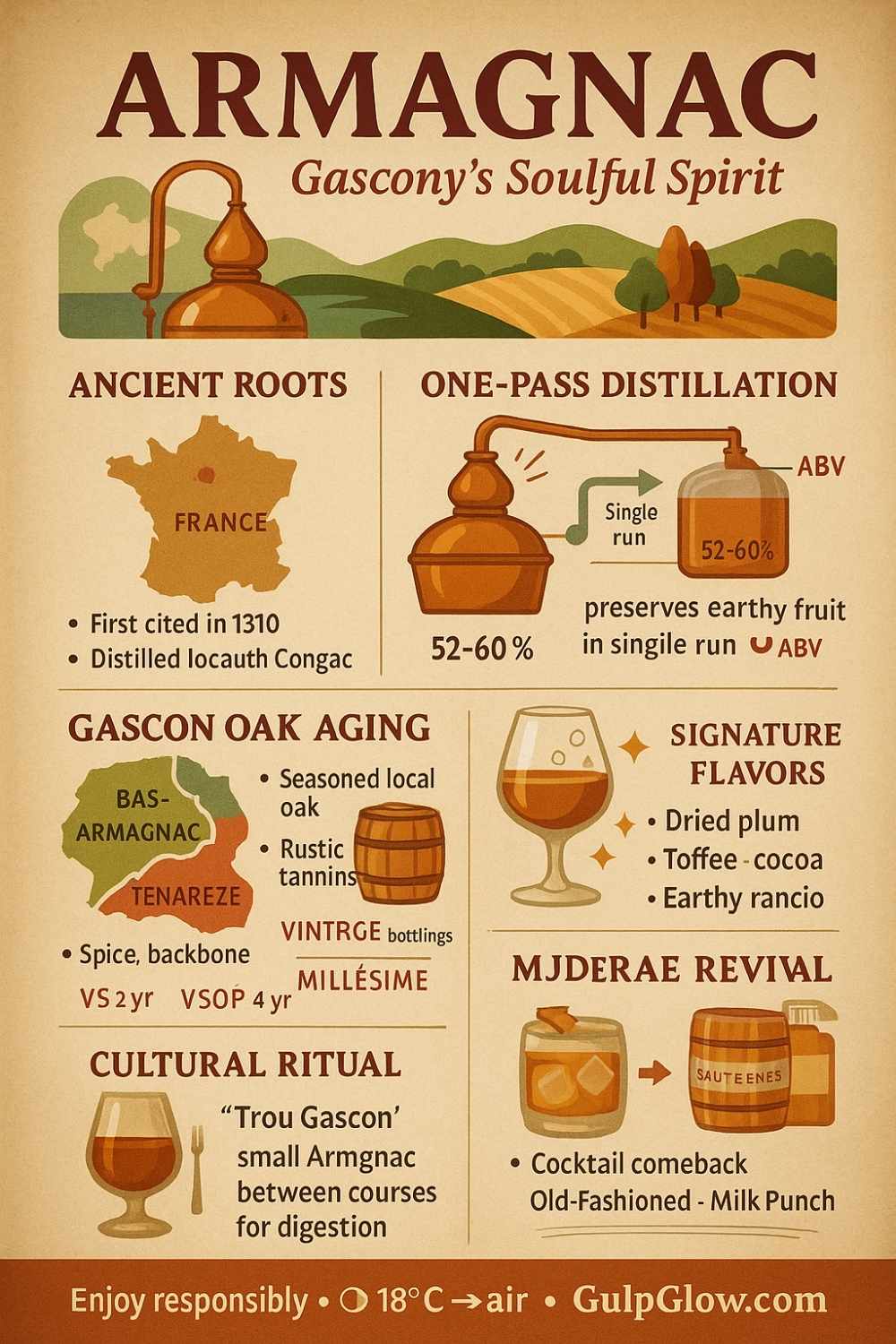

Armagnac: Gascony’s Soulful Spirit

One hundred miles south of Cognac, Armagnac quietly predates its more famous cousin, first cited in 1310 texts. Produced in the rolling Gascon countryside, Armagnac is distilled once in a continuous armagnacais still—an innovation resembling a copper locomotive—that preserves earthy fruit and robust texture in a single pass.

Gascony’s terroir divides into three regions: Bas‑Armagnac, with sandy soils yielding delicate prune and violet notes; Ténarèze, whose clay‑limestone produces fuller, spicier spirits; and Haut‑Armagnac, a rarer zone marked by limestone ridges and bright fruit tones.

Distillation & Aging Traditions

Distillation occurs soon after harvest to capture freshness. The low‑ABV spirit (52–60 %) enters seasoned Gascon‑oak casks rich in tannins that bestow amber color and a signature rustic edge. While VS and VSOP designations mirror Cognac’s minimum ages, Armagnac’s hallmark is vintage bottling—single‑harvest expressions aged decades in silence before release, allowing drinkers to taste a specific year’s climate.

Flavor & Culture

Expect dried plum, toffee, cocoa, and an earthy rancio that deepens with age. Bas‑Armagnac often shows graceful dried‑orchard fruit, whereas Ténarèze delivers peppery backbone suited to cigar pairings. Locals savor a small glass as a “trou Gascon,” a palate‑cleansing interlude between meal courses said to aid digestion.

Modern Revival

Craft producers now experiment with cask finishes—Sauternes, Banyuls, even craft‑beer barrels—without compromising tradition. As bartenders rediscover its depth, Armagnac appears in twists on Old‑Fashioneds and Milk Punches, offering complexity where bourbon’s sweetness or Cognac’s polish might be too restrained.

Pisco: The Spirit of the Andes

High in the arid valleys along Peru’s and Chile’s Pacific slopes, sun‑drenched vineyards give birth to Pisco—a crystalline brandy whose identity is fiercely protected and passionately debated. Unlike its European cousins, Pisco is typically bottled unaged, allowing the pure fragrance of Muscat‑family grapes to shine in every sip.

Origins & Denominations

Peru and Chile both claim historical primacy. Peruvian law defines “Denomination of Origin Pisco” as spirit distilled in copper pot stills to bottling strength (38–48 % ABV) with no water added and absolutely no barrel aging. Eight authorized grape varieties split into aromatic (Italia, Torontel, Albilla, Moscatel) and non‑aromatic (Quebranta, Mollar, Negra Criolla, Uvina) categories.

Chile, by contrast, permits column stills, optional oak contact, and proof adjustment with de‑mineralized water. Its labeling tiers—Corriente, Especial, Reservado, Gran Pisco—indicate rising ABV rather than age. These regulatory divergences produce distinct spirits even before the inevitable cultural rivalry over who invented the Pisco Sour.

Production Methods

Peruvians employ a single, slow distillation of freshly fermented wine, striving to capture the heart cut brimming with floral esters. The spirit then rests briefly in inert vessels (stainless steel or glass) to integrate before bottling. Chilean distillers may use multiple distillations and can mature spirit briefly in wood, lending faint vanilla or spice.

Styles & Flavor Profiles

- Puro (single‑grape) highlights varietal purity—Quebranta delivers earthy banana, Italia bursts with jasmine and orange blossom.

- Acholado blends grape varieties for complexity—think layered tropical fruit over peppered citrus.

- Mosto Verde distills partially fermented must, sacrificing yield for velvety texture and heightened sweetness.

Serving & Signature Cocktails

Sip premium Pisco neat at cellar temperature to appreciate lychee, honeysuckle, or cocoa husk nuances. Cocktail culture centers on the Peruvian Pisco Sour—lime, simple syrup, egg white, bitters—and Chile’s Piscola (Pisco‑Cola highball). Bartenders also riff with the Capitan (a Manhattan analogue) and modern infusions using herbs or cocoa nibs.

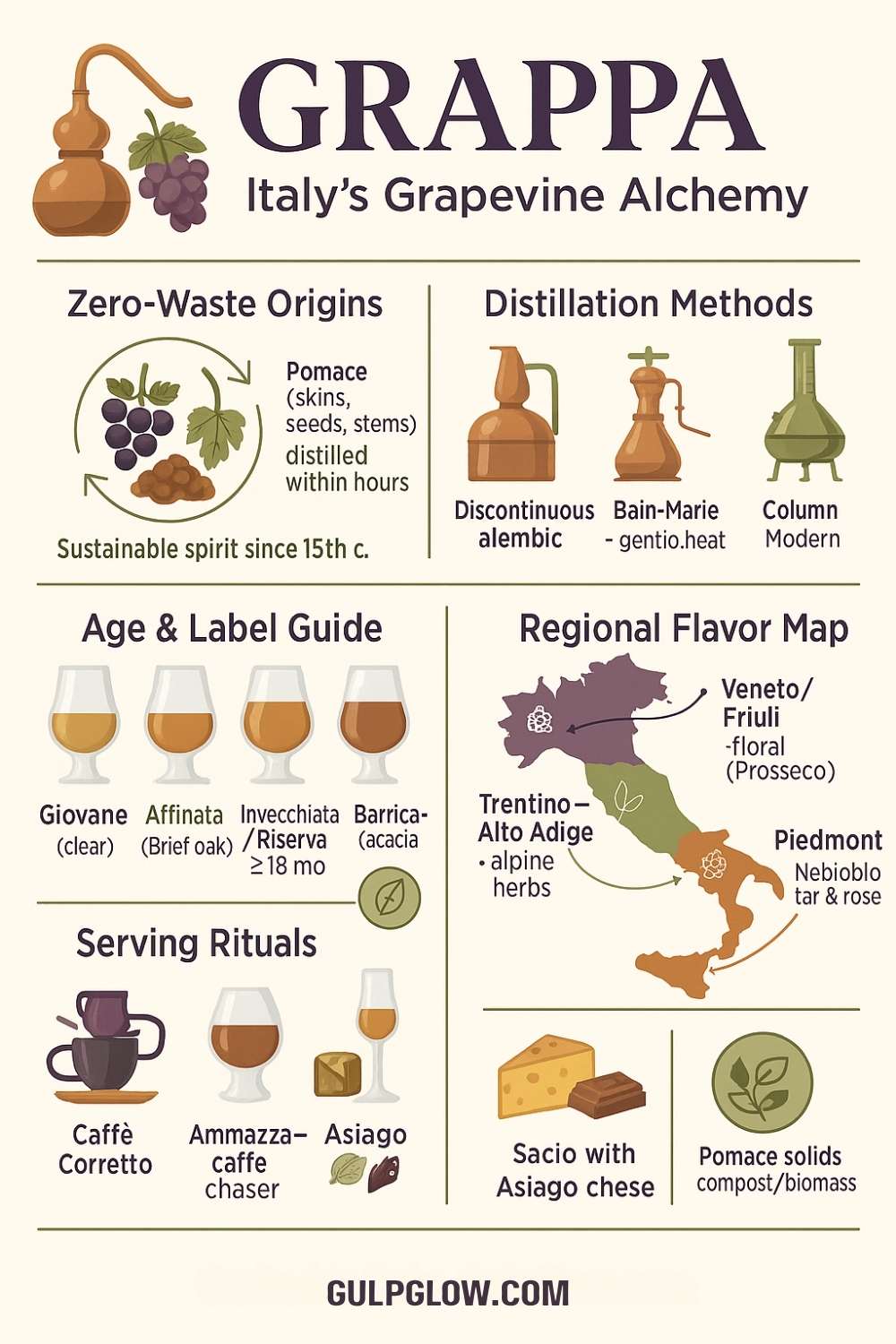

Grappa: Italy’s Grapevine Alchemy

Italy’s answer to sustainable distillation, Grappa transforms what remains after winemaking—skins, seeds, and stems—into a spirit redolent of vineyard terroir and artisanal ingenuity. Born in Alpine farmyards as a frugal digestivo, today’s Grappa has ascended to Michelin‑table stature and holds protected EU status (IGT) safeguarding its Italian provenance.

Pomace Origins & Zero‑Waste Ethos

Fresh pomace (vinaccia) arrives warm from grape presses and must be distilled swiftly to retain vitality. White‑wine pomace carries juice, necessitating delicate extraction, while red‑wine pomace’s fermentation lends deeper tannins and color.

Nothing is discarded—the leftover solids become compost or biomass fuel, encapsulating a circular‑economy model centuries ahead of its time.

Distillation Techniques & Aging

Traditional discontinuous alembics heat pomace on a perforated plate, percolating steam through skins to release alcohol vapors. Bain‑marie or water‑bath systems apply gentle, indirect heat, preserving fragile aromatics—ideal for Moscato or Gewürztraminer grappas. Modern continuous columns enhance efficiency for larger volumes.

Most Grappa is bottled giovane (young), crystalline, and fiery yet fragrantly grapey. Oak‑aged expressions—Affinata, Invecchiata/Riserva (>18 months), or acacia‑cask “Barricata”—introduce honey, vanilla, and sweet‑spice complexity, softening the spirit’s assertive edge.

Regional Styles & Pairings

- Veneto & Friuli: elegant, floral, often crafted from Prosecco or Pinot Grigio pomace.

- Trentino‑Alto Adige: mountain‑herb nuances, sometimes matured in chestnut casks.

- Piedmont: Nebbiolo grappa echoes Barolo’s tar and rose; Moscato versions explode with orange blossom.

Enjoy Grappa as a caffè corretto shot into espresso, an ammazzacaffè chaser after coffee, or sipped alongside aged Asiago cheese and dark chocolate.

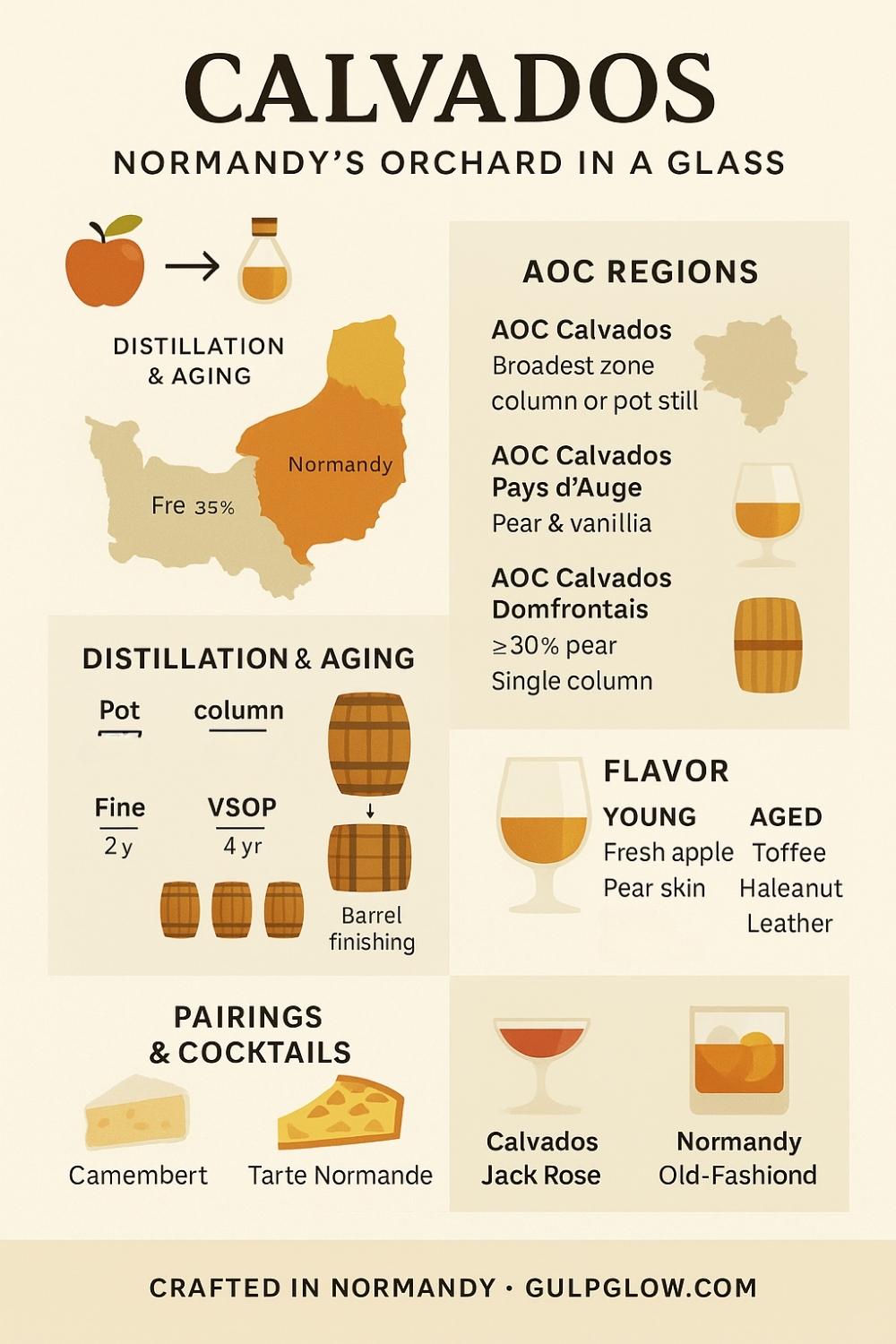

Calvados: Normandy’s Orchard in a Glass

Where sea breezes meet lush apple orchards, Normandy distillers coax cider into Calvados—a brandy that marries crisp fruitiness with gentle oak, conjuring memories of tarte tatin and autumn bonfires. Three appellations govern style diversity, each linked to soil, apple variety, and distillation method.

Apple Varieties & AOC Regions

- AOC Calvados: broadest zone; column or pot stills; at least 35 % bitter or bittersweet apples balanced by sweet and sharp varieties.

- AOC Calvados Pays d’Auge: chalk‑rich soils; mandatory double pot distillation; celebrated for refined pear and vanilla notes.

- AOC Calvados Domfrontais: high pear content (≥30 %); single column distillation; delivers floral, juicy profiles.

Over 200 cider apple cultivars contribute tannin, acid, and sugar matrices—Domaine, Bedan, and Binet Rouge among them—picked, pressed, and fermented over winter before distillation.

Distillation & Aging Classifications

Calvados from pot stills usually undergo two distillations to about 70 % ABV, while column stills yield lighter spirit near 72 %. Aging in French oak lasts a minimum of two years (Fine), four years (VSOP), or longer than six (Hors d’Âge). Producers may employ old Cognac, bourbon, or sweet‑wine barrels for finishing, layering dried‑fruit, caramel, or spice undertones.

Flavor, Pairings & Cocktails

Young Calvados bursts with fresh apple, pear skin, and white blossom; extended aging adds toffee, hazelnut, and leather. Traditional Normandy pairings include Camembert or tarte Normande. Mixologists champion the Calvados Jack Rose and Normandy Old‑Fashioned, while chefs deglaze pork chops or flambé crêpes with aged Calvados for orchard‑laden depth.

Orchard freshness, sustainable roots, and protected origin make Calvados a spirited ambassador of northern France—proof that great brandy can bloom wherever fruit meets craft.

Fruit Brandies & Eaux‑de‑Vie

Brandy’s spectrum extends well beyond grapes and apples. Across Central and Eastern Europe—indeed anywhere orchards thrive—distillers capture the raw perfume of cherries, plums, pears, raspberries, and even apricots in crystal‑clear spirits called eaux‑de‑vie (French for “water of life”). Unlike oak‑matured Cognac or Calvados, these brandies are almost always bottled unaged, preserving the fruit’s volatile esters in vivid clarity.

Core Styles & Regional Identities

- Kirsch/Kirschwasser (Germany, Switzerland): distilled from Morello cherries with stones, lending almond‑marzipan nuance alongside bright cherry skin.

- Slivovitz (Czechia, Serbia, Croatia): plum brandy fermented with skins; long pot distillations yield earthy dried‑fruit depth— often enjoyed at weddings and holidays.

- Poire Williams (France, Switzerland): Bartlett/Williams pears produce a luscious, floral eau that can be bottled with a whole pear grown inside.

- Obstler (Austria, Germany): field blend of apples, pears, and stone fruit, resulting in a balanced orchard medley.

Distillation typically occurs on small copper pot stills not unlike those used for grappa. Because no barrels mask imperfections, only pristine, fully ripe fruit and exacting cuts produce a clean, expressive spirit.

Serving Traditions & Culinary Uses

Fruit brandies are ideally served chilled (8–12 °C) in narrow tulip glasses to concentrate delicate aromas. In Alsace they punctuate a rich meal as digestif; in the Balkans, a shot of slivovitz accompanies meze or hearty stews.

Bakers soak sponge cakes in Kirsch for Black Forest gâteau, while bartenders deploy Poire Williams in aromatic twists on the French 75 or Collins. Whether sipped neat or splashed into cuisine, these eaux‑de‑vie offer the purest conduit between orchard and palate.

Choosing & Tasting Brandy

With so many styles populating shelves, selecting the right bottle can feel overwhelming. A methodical approach—considering category, age, flavor profile, and intended use—turns decision paralysis into confident curation.

Decoding Labels & Age Terms

- Category First: Identify grape brandy (Cognac, Armagnac), pomace (Grappa), or fruit (Calvados, Kirsch). Each obeys unique rules that shape flavor.

- Age & Quality Marks: VS/VSOP/XO codes signal minimum cask years; “Napoléon,” “Reserva,” or vintage statements often exceed those baselines. In fruit brandies, look instead for distillation year and fruit variety.

- ABV & Cask Info: Higher proof (45–60 %) can intensify aromatics but may require dilution. Cask finishes (sherry, port) add sweetness and spice.

Glassware, Service & Sensory Technique

- Glass Choice: A tulip or copita concentrates volatile aromatics better than a wide brandy snifter which can dissipate them too quickly.

- Temperature: 18 °C for aged grape brandies; lightly chilled for clear fruit eaux‑de‑vie; never overly warmed by hand—excess heat drives off subtleties.

- Tasting Steps: Observe color/legs, nose gently from rim to center, take a small sip to coat palate, then note evolution on finish. Add a drop of water only to cask‑strength expressions.

Pairings & Cocktail Deployment

- Food: Blue‑veined or washed‑rind cheeses with Cognac, charcuterie with Armagnac, dark chocolate with Calvados, dried figs with Pisco Mosto Verde.

- Cocktails: Sidecar, Vieux Carré (Cognac), Pisco Sour, Jack Rose (Calvados), Grappa Negroni twist—each leverages a brandy’s balance of fruit, acid, and warmth.

Practicing comparative tastings—say, VSOP Cognac next to four‑year Armagnac—sharpens one’s sensory memory and uncovers how terroir and technique manifest in the glass.

Glossary & Further Resources

Essential Terms

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Eau‑de‑vie | Clear fruit brandy distilled to capture pure aromatics; typically unaged. |

| Charentais Still | Onion‑shaped copper pot still used for Cognac’s double distillation. |

| Armagnacais Still | Continuous copper column unique to Armagnac, producing robust spirit in one run. |

| Angel’s Share | Portion of spirit lost to evaporation during barrel aging. |

| Rancio | Nutty, oxidative flavor found in long‑aged brandies (XO, vintage Armagnac). |

| Mosto Verde | Pisco distilled from partially fermented must for richer mouthfeel. |

| Vinaccia | Italian term for grape pomace—the raw material of Grappa. |

Books & Online Hubs

- Cognac: The Story of the World’s Greatest Brandy by Nicholas Faith

- Pisco: The Spirit of Peru by Jorge R. Camorra

- Armagnac: The Definitive Guide by Charles Neal

- Whisky Advocate’s brandy columns and /r/brandy subreddit for reviews and community tasting notes

Tasting Experiences

- House tours at Hennessy (Cognac) or Delamain for barrel‑room education.

- Armagnac Route des Cèdres driving tour through Bas‑Armagnac vineyards.

- Pisco trail distillery visits in Ica and Elqui Valleys.

- Calvados distillery cycling paths in Pays d’Auge orchards.