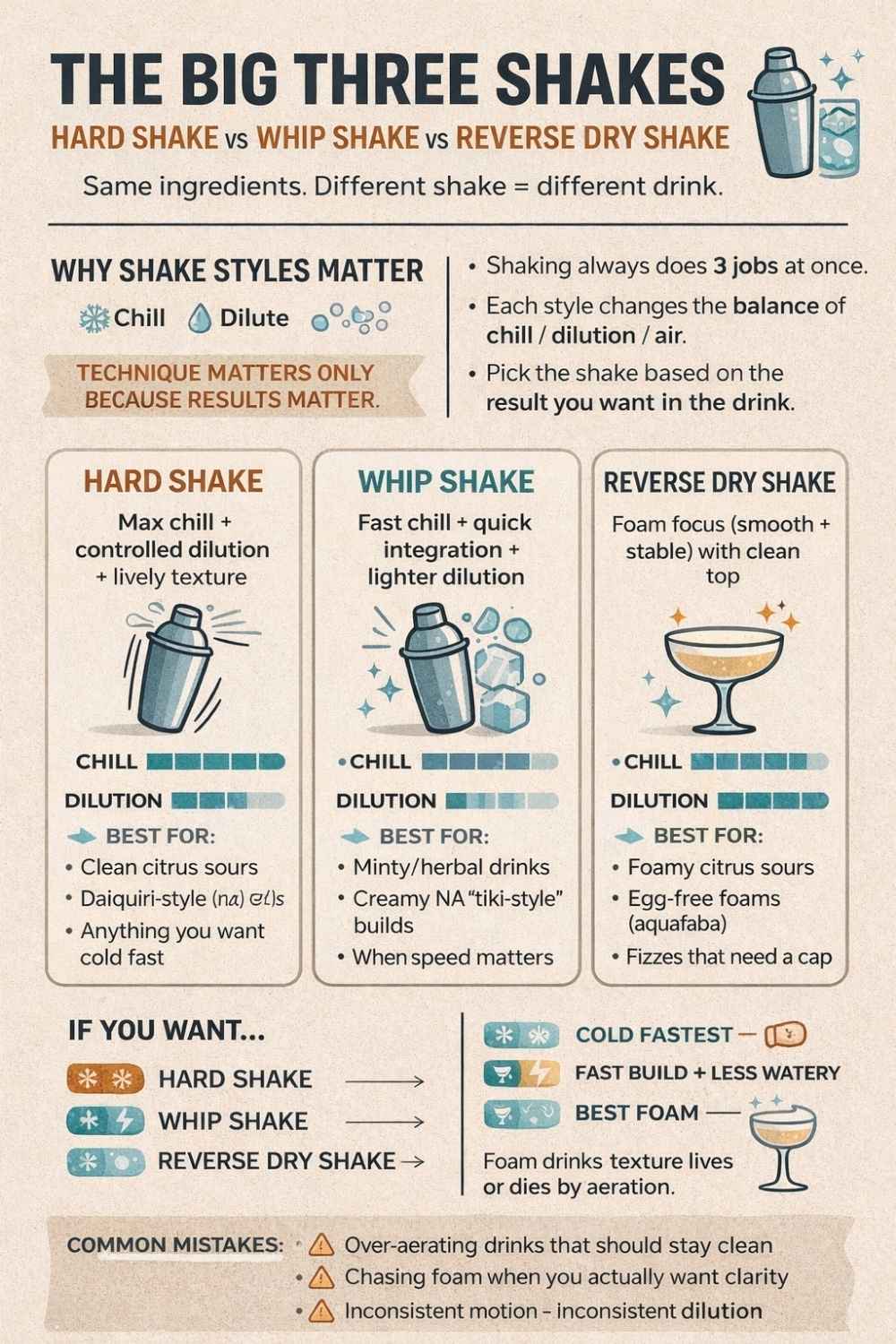

The Big Three Shakes Explained: Hard Shake vs Whip Shake vs Reverse Dry Shake

If you’ve ever made the same cocktail twice and wondered why one felt lighter, colder, or more textured than the other, the answer is often the shake. Not the recipe. Not the spirits. The shake.

Over time, bartenders developed different shake styles to solve different problems: how to chill without overdiluting, how to build foam fast, how to get a denser texture in egg white drinks. That’s where the hard shake, whip shake, and reverse dry shake come in. Each one pushes the drink in a specific direction.

This guide explains what each shake is meant to do, when to use it, and what actually changes in the glass—hydration, texture, and speed. Once you understand the intent behind each technique, choosing the right shake becomes automatic, and your drinks start tasting more deliberate instead of coincidental.

Why Shake Styles Matter (and Why They’re Not All the Same)

Before getting into named techniques, it helps to reset how shaking actually works. Shaking is doing three jobs at once: chilling, diluting, and introducing air. Every shake style simply changes the balance between those three outcomes.

A Daiquiri wants fast chilling and clean dilution with minimal foam. A Ramos Gin Fizz needs extreme aeration without flooding the drink with water. An egg-white Sour lives or dies by foam density and texture. One generic shake can’t optimize all of those goals at the same time.

That’s why different shake styles exist. They’re not flair or tradition for tradition’s sake—they’re responses to specific structural needs in a drink. Once you understand what each shake prioritizes (air, water, or control), the technique stops feeling academic and starts feeling obvious.

This section-by-section breakdown focuses on intent first, mechanics second. Technique only matters insofar as it gets you the result you want in the glass.

Hard Shake

The hard shake is about refined aeration with controlled dilution. Popularized by Japanese bartenders, it emphasizes ice movement inside the shaker rather than brute force. The goal is to circulate the liquid smoothly around the ice so it chills evenly and incorporates fine air bubbles without breaking the drink apart.

Before the mechanics matter, the purpose matters: the hard shake aims to create a silky, cohesive texture—especially useful in drinks with egg, cream, or citrus that benefit from subtle lift rather than visible foam.

Purpose & Mechanics

The hard shake uses a three-point or figure-eight motion that keeps ice rolling through the liquid instead of slamming end-to-end. This rolling action creates gentler aeration and more uniform chilling.

Key characteristics:

- Ice stays in motion rather than colliding violently

- Air is incorporated finely, not explosively

- Emulsion stays stable rather than frothy

This is not about shaking longer—it’s about how the liquid moves.

Timing, Ice & Dilution

- Timing: ~10–12 seconds

- Ice: One large cube plus one or two smaller cubes works well

- Dilution: Moderate and controlled

Because the ice isn’t being shattered, dilution increases steadily rather than spiking. That makes the hard shake useful for cocktails served up, where excess water is hard to hide.

Drink Matches

- Clover Club

- Whiskey Sour / Pisco Sour (especially when followed by a dry or reverse dry stage)

- Cream-based or egg-based sours

These drinks benefit from texture without looking whipped. Always follow with a double strain to remove micro-chips and keep the surface clean.

Pros & Limitations

Pros

- Polished mouthfeel

- Fine, stable aeration

- Visually elegant results

Limitations

- Requires practice

- Slower than other shake styles

- Results can overlap with a well-executed standard shake

Used well, the hard shake rewards control. Used poorly, it’s just an inefficient regular shake.

Whip Shake

The whip shake exists to do one thing extremely well: build aeration fast with minimal dilution. Instead of a full load of ice, you use one or two small cubes (or a bit of crushed ice) and shake until the ice completely melts.

The intent matters here. Whip shaking is not designed for drinks served “up.” It’s designed for drinks that will be finished over fresh ice, where additional dilution is expected later.

Purpose & Mechanics

By using very little ice, the whip shake:

- Chills quickly

- Aerates aggressively

- Adds minimal water during the shake itself

Once the ice disappears, you stop. That melt-out moment is the cue.

Timing, Ice & Dilution

- Timing: ~5–8 seconds (until ice vanishes)

- Ice: 1–2 small cubes or crushed ice

- Dilution: Low during shake; total dilution happens in the glass

This is why whip shakes pair naturally with crushed-ice service.

Drink Matches

- Ramos Gin Fizz (initial shake stage)

- Tiki drinks served over crushed ice

- Speed-focused egg white sours

For Ramos-style drinks, the whip shake replaces minutes of shaking with seconds—foam gets built early, then the drink finishes itself in the glass.

Pros & Limitations

Pros

- Extremely fast

- Massive aeration

- Minimal shaker dilution

Limitations

- Under-chills drinks served up

- Easy to overshoot if you miss the melt cue

Whip shaking is purposeful efficiency. If the drink isn’t meant to keep diluting in the glass, this isn’t the right tool.

Reverse Dry Shake

The reverse dry shake flips the classic egg-white workflow. Instead of shaking without ice first, you shake with ice, strain it out, then shake again without ice to build foam.

The motivation is foam quality. Many bartenders find that whipping proteins when the liquid is already cold produces denser, glossier, longer-lasting foam.

Purpose & Mechanics

The sequence matters:

- Ice shake chills and dilutes the drink fully

- Ice is removed

- Second, iceless shake focuses purely on aeration

By separating chilling from foaming, you get more control over both.

Timing, Ice & Dilution

- Ice shake: 8–10 seconds

- Reverse dry (no ice): 5–8 seconds

- Dilution: Set during the first stage

The second shake adds air without adding water, which is why foam structure improves.

Drink Matches

- Whiskey Sour

- Pisco Sour

- Clover Club

- Any egg white or aquafaba sour

Always finish with a double strain to protect the foam cap from ice shards.

Pros & Limitations

Pros

- Dense, stable foam

- Better visual control

- More comfortable second shake (cold tins)

Limitations

- Extra step

- Slightly slower in high-volume service

Reverse dry shaking is about intent. When foam matters, this method removes guesswork.

Hydration, Texture & Speed — What Actually Changes in the Glass

Instead of thinking about shake styles as techniques, it’s more useful to think of them as biases. Each shake leans the drink toward a specific outcome: more water, more air, or more control.

The hard shake biases toward balance. It introduces air gently while keeping dilution predictable. The result is a drink that feels cohesive and polished rather than whipped.

The whip shake biases toward speed and aeration. It adds very little water during the shake itself and relies on service ice to finish dilution. That makes it fast and frothy—but only appropriate when the drink is designed for it.

The reverse dry shake biases toward foam quality. Dilution happens first, foam second. This separation is what produces dense, glossy caps that last.

Quick comparison

| Shake style | Dilution control | Aeration style | Speed | Best outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hard shake | Moderate, steady | Fine, subtle | Slowest | Silky texture |

| Whip shake | Very low (initial) | Aggressive, light | Fastest | Fast foam + lift |

| Reverse dry shake | Set in stage one | Dense, structured | Medium | Stable foam |

If a drink tastes “off,” it’s usually because the shake biased the wrong variable—not because the recipe was wrong.

Choosing the Right Shake (Without Overthinking It)

When deciding how to shake, don’t start with technique names. Start with the drink’s structure.

Ask yourself how the drink finishes.

If it’s served up, the shake needs to fully chill and dilute the drink on its own. That points you toward a hard shake or a reverse dry shake.

If it’s served over crushed ice or topped with soda, the shake doesn’t need to finish the job. That’s where the whip shake shines—it front-loads aeration and lets the glass take care of the rest.

Now consider foam.

Egg white or aquafaba immediately narrows the field. If foam quality matters visually or texturally, reverse dry shaking gives you the most control. If speed matters more than perfection, whip shaking is often “good enough.”

Most of the time, the correct shake becomes obvious once you stop asking what’s fancy and start asking what’s functional.

Technique Details That Matter More Than the Name

A perfectly executed “basic” shake will outperform a sloppy hard shake every time. These variables quietly do most of the work:

Ice quality

Clear, cold, solid ice melts predictably. Wet or cracked ice doesn’t.

Ice amount

Too much ice limits aeration. Too little prevents proper chilling.

Cadence

Smooth, repeatable motion beats frantic shaking. Ice should move through the liquid, not just collide.

Total time

More shaking isn’t better. Each drink has a narrow window where chill, dilution, and air align.

Named techniques guide intent—but fundamentals decide outcomes.

Common Mistakes (and What They Usually Mean)

A few patterns show up again and again:

If a drink tastes thin and watery, the issue is almost always too much dilution, not the recipe. Shorten the shake or change styles.

If foam collapses quickly, look for ice shards or warm ingredients. Reverse dry shake and double strain.

If a whip-shaken drink feels under-chilled, it’s likely being served up instead of over ice. The shake did its job—the service didn’t.

If a hard shake feels indistinguishable from a regular shake, the ice or motion probably isn’t doing what you think it is.

Treat mistakes as feedback, not failure. The drink is telling you what it needs.

A Simple Practice Exercise (Worth Doing Once)

If you want to internalize the differences, try this side-by-side:

Make a Whiskey Sour twice.

- First with a classic dry-then-wet shake

- Then with a reverse dry shake

Don’t rush. Look at the foam. Touch it. Watch how long it lasts.

Then make a Ramos-style Gin Fizz once with a whip shake and once with a full ice shake. Time both. Feel the difference in effort and texture.

One short session like this will teach you more than memorizing rules.

Final Takeaway

These three shakes aren’t competing techniques—they’re solutions to different problems.

The hard shake gives you refinement.

The whip shake gives you speed and lift.

The reverse dry shake gives you foam you can trust.

Once you stop treating them as tricks and start treating them as tools, your drinks stop feeling improvised and start feeling intentional.